|

|

|

|

|

|

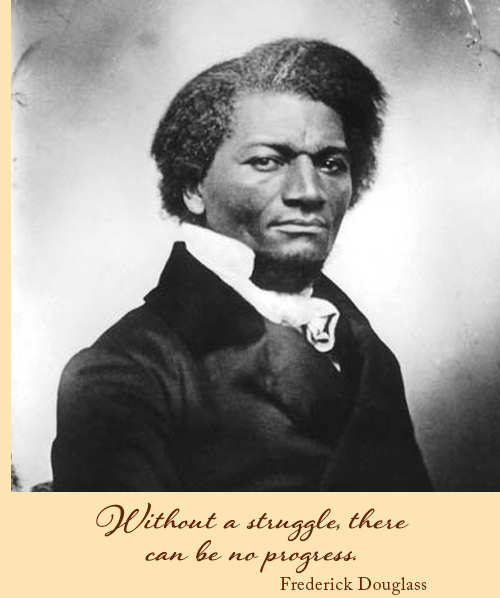

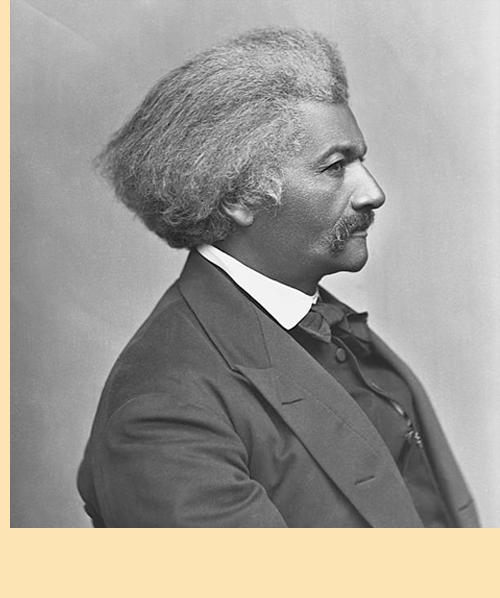

Frederick Douglass was born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey in Talbot County, Maryland in 1818. His mother was a slave named Harriet Bailey, who brought him into the world in the cabin of her mother, Betsy Bailey, also a slave but whose husband was free. The cabin was next to a small ravine on the Tuckahoe Creek near what is now called the village of Cordova. It was on the property called Holme Hill Farm owned by their owner, Aaron Anthony. Frederick’s mother soon returned to the farm where she worked, and he only saw her a few times thereafter; she died when he was eight.

Frederick lived with his grandmother until he was six, and then was moved to the much larger Wye House plantation where his owner, Aaron Anthony, was employed as an overseer. Anthony died within two years, and Frederick came into the possession of Thomas Auld, Anthony’s son-in-law. He was sent by Auld’s wife to her sister-in-law in Baltimore, Sophia Auld. He was recognized as a gifted young boy, and Sophia began to teach him the alphabet, and to read, although doing so was illegal. Her husband Hugh Auld discovered his wife’s actions and insisted that she stop. He warned that if a slave were to read, he would learn enough to want to be free. Frederick overheard, and later described the statement as a “decidedly antislavery lecture,” one that made him resolve to continue to learn to read, and to become free.

Frederick did continue learning – from white children in the neighborhood – and began reading everything he was able to see or to get into his possession. The Columbian Orator, a lesson book designed for classical education and public speaking, taught him the derivation of much of western philosophical thought from Greek and Latin literature, and taught him as well a great deal about freedom and human rights. It also taught him the principles of classical writing which he applied throughout his life in preparing the speeches for which he became world famous.

By then Frederick was owned by Colonel Lloyd, owner of the Wye House plantation, and was hired away by farmer William Freeland. He began to conduct a weekly Sunday school, teaching other slaves to read the New Testament, until after about six months a mob of slave owners stormed in to break up the meeting. Frederick began to form in his mind his life’s mission.

When Frederick was about sixteen, he was placed under the control of Edward Covey, a small farmer reputed to have the ability to break a slave’s spirit. Frederick was whipped repeatedly, and very nearly was “broken” in spirit until one day he fought back – defensively, not striking Covey, because that would likely have gotten him severely punished, possibly killed – but by simply fending off the farmer’s attack. The contest lasted about two hours, when Covey called it off, and he never attempted to beat Frederick again.

|

|

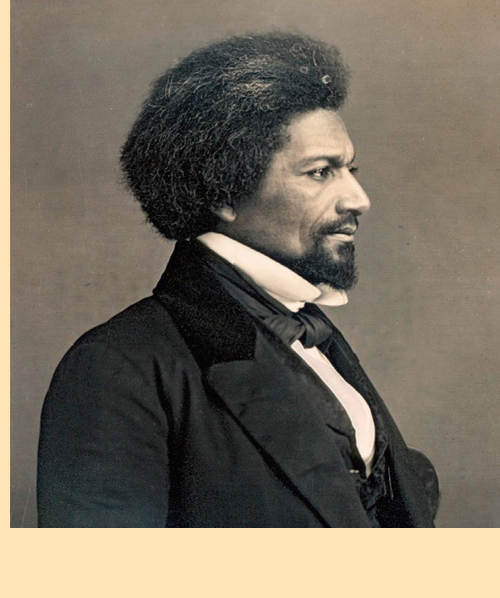

Frederick had tried to escape several times – from William Freeland, and later from Edward Covey, and he was severely punished. After one attempt he had been sent to jail in Easton. Later, in 1838 he managed his successful escape with a great deal of help from friends. He had borrowed a sailor’s uniform, and obtained papers that identified him as a seaman. He boarded a train in Baltimore and traveled to Havre de Grace, crossed the Susquehanna River by ferry, and then continued by train to Wilmington, Delaware, from there to Philadelphia by steamboat, and from there to New York City, again by train. Of New York he later wrote, “A new world had opened upon me…It was a time of joyous excitement which words can but tamely describe…”

Immediately after his arrival in New York, he married a free African American woman he had met in 1837 in Baltimore and who came to New York with him, Anna Murray. As a slave, of course, he would not have been permitted to marry without his master’s consent. To avoid being discovered and returned to slavery, he stopped using the last name Bailey, and called himself Frederick Johnson. The newlyweds moved on north to New Bedford, Massachusetts, and were assisted by a black couple, Mary and Nathan Johnson, who were associated with the abolitionist movement.

Frederick decided to change his last name again, and asked Nathan Johnson to choose a new one for him. He insisted, however, that he keep his first name. Johnson had been reading Sir Walter Scott’s epic narrative poem The Lady of the Lake, a literary sensation of the nineteenth century. He picked the name of the leader of the Scottish clan Douglas, one of the poem’s key figures. Frederick chose to spell his new last name with a slight difference – a double‘s’. With his new wife Anna he thus adopted the new name he would keep for the rest of his life and would make world famous – Frederick Douglass.

Frederick and Ann’s first child, Rosetta, was born in 1839 in New Bedford. They would eventually have four more children together: sons Lewis Henry, Frederick Jr., Charles Remond, and daughter Annie. In New Bedford he joined and became a licensed preacher in the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church and he began, as well, to attend abolitionist meetings. He met William Lloyd Garrison and was encouraged to speak, at first informally, then as a featured guest at the annual convention of Garrison’s Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. He was only 23, but was already becoming an accomplished and eloquent public speaker.

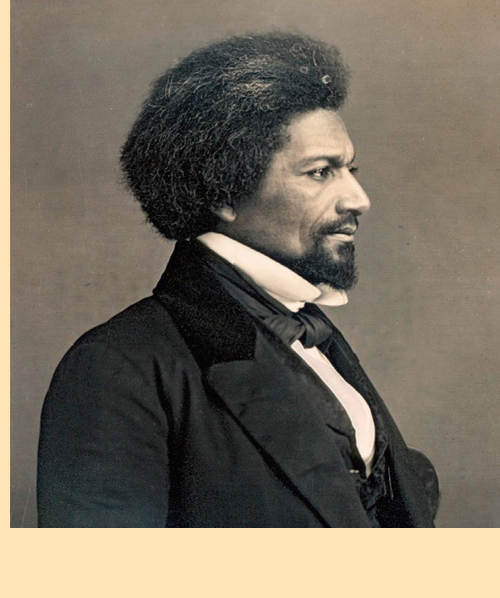

Douglass was hired as a speaker by the Society, and later joined a tour by the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1843 that spanned six months and traveled over much of the Northeast and Midwest. His fame was growing, and he gained a large following of admirers, speaking often to packed houses. Garrison, the society’s founder, was also quite interested in advancing the rights and the role of women, and included them on a virtually equal basis with men in his organizations – something almost unheard of in 19th Century society in Europe and America. Douglass thus became familiar with, and aided, the cause of women’s rights with his eloquence while advancing the cause of abolition. While on a speaking tour he met Susan B. Anthony, and eventually supported the women’s equal rights cause as expressed by Elizabeth Cady Stanton at the Seneca Falls Convention held in 1848.

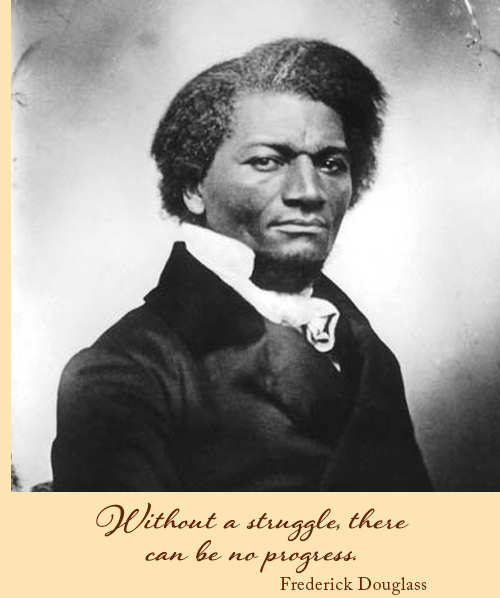

In 1845, when he was only 27, he wrote and published the first of his three autobiographies, his Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. It was an immediate sensation and was reprinted numerous times. It was soon translated into Dutch and French, and was then circulated widely in Europe.

|

|

The book was so successful that in August of 1845 Douglass decided to embark on a tour of the British Isles, for the very practical reason that he was still, in fact, an escaped slave, and as long as he remained in the United States he was in danger of being seized and returned to his master. He was lionized in Ireland and England, made many speeches to packed houses, and was extremely successful in building support there for the abolition of slavery in America.

It has been said that years later, during the American Civil War, the British government wanted to intervene in the name of restoring peace. They knew this could permanently separate the United States into two nations, and that both would be much reduced in power and influence. The British would likely have entered on the side of the Confederacy, the source of cotton for their enormous cloth industry, but they could not do it because of two factors, some say: the overwhelming sentiment against slavery that Frederick Douglass had helped to inspire among the British people in the mid-1840s, and the Emancipation Proclamation, issued by Abraham Lincoln in September, 1862.

Douglass’ speeches may indeed have been a factor. His British friends so admired him that they purchased his freedom from his owner, and he was able to return to the United States as a free man in 1847.

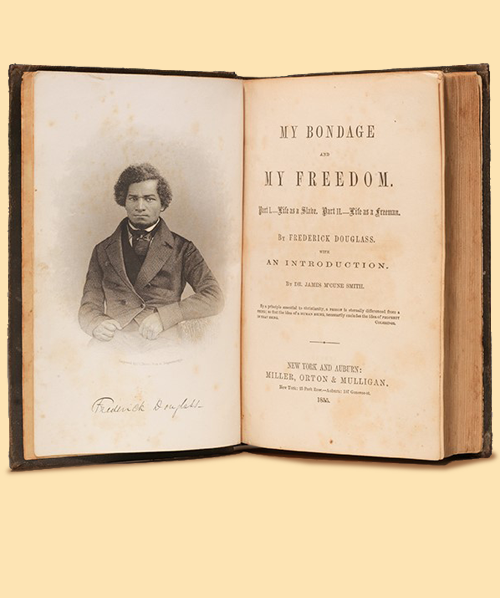

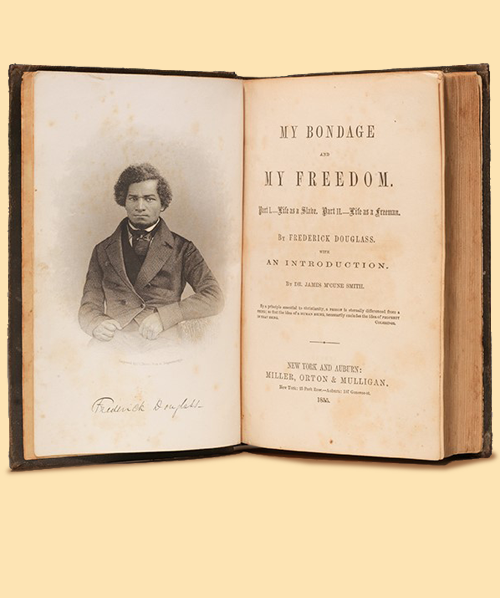

By the time he sailed back to the U.S., Douglass had gained huge fame and admiration among Americans who supported the abolition of slavery. He continued his oratory in far-flung places, and became one of the North’s most sought-after speakers. He settled in Rochester, New York, and began to publish The North Star, the first of a number of newspapers he published during his long career. He frequently spoke strongly in favor of improving the education of free black students, and education became one of his foremost causes for the rest of his life. In 1855 he published another autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom. It was eventually translated into German, and it was widely circulated in America and Europe.

Among the famous people he came to know in his wide travels was John Brown, who had been trying to start an armed rebellion among slaves in the South. They met in 1848, and Douglass, though friendly with Brown, opposed his violent approach, and believed that his attack in 1859 on the federal armory in Harper’s Ferry would cause a negative reaction among many people who might otherwise support the cause of abolition. Brown’s raid failed, and he was caught, tried, convicted and hung. Douglass, who had corresponded with and visited with Brown, was sought as a co-conspirator. In order to avoid capture by federal forces he fled to Canada, and shortly thereafter, to England, where he had planned to make another speaking tour. In 1860 his young daughter Annie died, and he returned to the United States and was not charged.

In late 1860 Abraham Lincoln was elected president. South Carolina soon seceded, followed by six more Southern states before Lincoln was inaugurated in March, 1861. The Confederate attack on Fort Sumter in South Carolina led to Lincoln’s call for an army of volunteers from each of the states, which was followed by the secession of four more Southern states. The Civil War had begun.

|

|

Frederick Douglass was a strong advocate of African American service in the war. He argued that since the war was being fought to end slavery, African Americans should be allowed to fight for their freedom and for that of all of their people. The nation was slow to accept the reasoning of Douglass and his co-advocates, however, and many battles were fought and many soldiers’ lives were lost before African American men were seen to be needed for the war effort. They proved, ultimately, to be indispensable.

The first African American unit to see significant action was the famous 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment and Douglass served as a recruiter. His son Frederick Douglass Jr. also was a recruiter, and his other son Lewis Douglass fought with the 54th at its most famous engagement – the Battle of Fort Wagner, near Charleston, South Carolina. Its commander, Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, who was a member of a prominent Boston abolitionist family, was killed, as were 29 of his men, all African Americans. Twenty-four later died of wounds, 15 were captured, and 52 were missing in action and never accounted for. An additional 149 were wounded.

Although the Massachusetts 54th was not able to achieve its goal of defeating the Confederate defenders of Fort Wagner, it was enormously respected for its valor, and the battle was considered ample evidence of the ability of African American soldiers to fight bravely and effectively. Before the end of the war, some 200,000 African American men were called to serve in the Union forces. Few knowledgeable Union commanders doubted their value in the winning of the American Civil War.

Douglass met twice with President Abraham Lincoln at the White House. In 1863 they discussed the issues of unequal pay and treatment of black soldiers; Douglass was extremely pleased at the friendly reception he was given by Lincoln, and by his understanding of the problem of achieving equal treatment. Douglass came away knowing Lincoln understood that, while the war was first about preserving the Union, and second about freeing the slaves, the first depended entirely upon the second. The pay issue was later resolved. Then in August of 1864 Lincoln asked Douglass to assist in preparations for aiding the escape of slaves from the South. The issue had become important since at that time the war’s outcome was still not clear. Victory at the Wilderness and other victories soon to follow transformed the outlook for the war, and made the escape plans unnecessary. Lincoln would be re-elected, the abolition of slavery would be won, and the Union preserved.

Douglass saw Lincoln one more time, at the White House reception in early March, following his re-inauguration. The occasion would be the first time a black person was admitted to such a reception. The White House guards attempted to follow their old practice of not allowing Blacks admission, and tried to usher Douglass and the black lady he was escorting to the party out a side exit rather than admit them. He saw a friend entering, and called on him to request Lincoln to order their admission; soon they were ushered into Lincoln’s presence, and once again he was very cordially greeted by the President.

One last time Douglass was invited to meet with Lincoln, this time on short notice on an evening at his retreat at the Soldiers Home. Douglass declined because of a previous speaking engagement, because he had made it a practice always to honor such promises rather than disappoint an assembled crowd. It was the last time he would have such an opportunity, because Lincoln was assassinated on April 14 of 1865. Douglass often expressed regret that he had not taken the opportunity to visit again with the man whom he had grown to greatly respect.

|

|

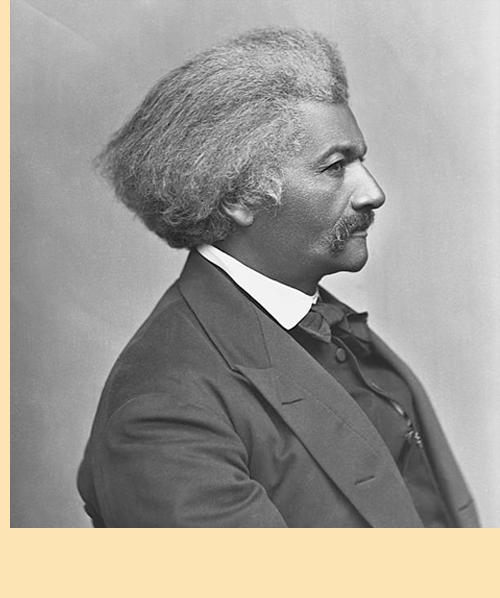

Soon the Civil War was officially over, and Douglass had achieved by then both national and world-wide respect. When Ulysses S. Grant took office in 1869, he appointed Douglass to the commission that was to investigate the possibility of annexing the Dominican Republic to the U.S. Much later he served as minister-resident and consul-general to the Republic of Haiti, as well as chargé d’affaires to the Dominican Republic.

Douglass continued to make public speeches, and to observe and participate in the nation’s rehabilitation after the dreadfully destructive war. He was elected to represent Rochester, N.Y. at the National Loyalist’s Convention, held in Philadelphia in 1866, and was the only black man who attended. It was composed, he said, of delegates from the South, North, and West, and its object was “to diffuse clear views of the situation of affairs at the South, and to indicate the principles deemed advisable by it to be observed in the reconstruction of society in the Southern States.” Its outcome was not what the delegates had hoped, in that they could not come to any constructive agreements, and it disbanded in frustration. Thereafter President Grant recommended the adoption of the 15th Amendment to the Constitution, which was adopted in 1870, and prohibited state governments from denying a citizen the right to vote based on that citizen’s “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

Although the intentions of the 15th Amendment were clear, it was not used to overcome the negative effects of the Ku Klux Klan and other similar organizations in the Deep South until the middle of the 20th century. Those organizations gained power, threw Republican officeholders out of office, limited Blacks’ ability to vote, and by a combination of laws and violence reestablished white supremacy and segregation, and disenfranchised black voters for generations.

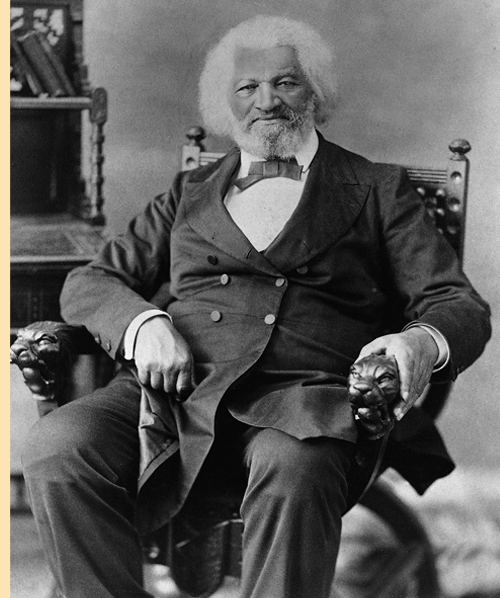

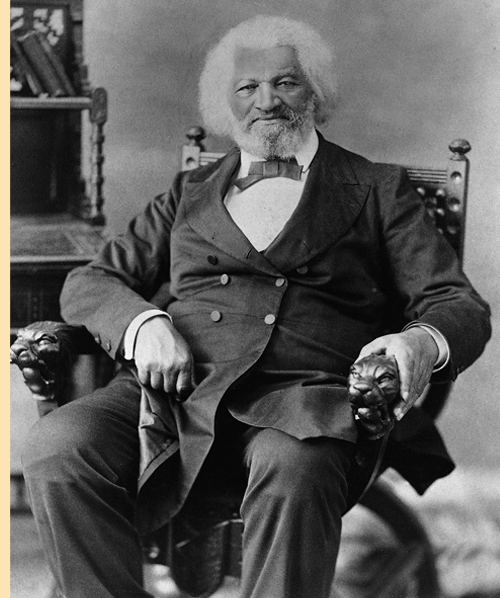

But in the Capital, Douglass persevered. In 1877 he was appointed U.S. Marshal of the District of Columbia by then-President Rutherford B. Hayes. After what has been called a “suspicious” fire consumed his home in Rochester, N.Y., he purchased a home in the Anacostia section of D.C. in 1878, and lived there until his death in 1895. The house is on a high hill and has a sweeping view of the city of Washington. Douglass renamed it Cedar Hill and rebuilt and expanded it; it is now a National Historic Site. President James Garfield, Hayes’ successor, in 1881 appointed one of his own friends to the U.S. Marshal post and made Douglass Recorder of Deeds for D.C., at the time a high-paying job.

In 1882, his wife of 44 years, Anna Murray Douglass died of a stroke. Douglass, it is said, went into a depression thereafter, until his friendship with Ida B. Wells, an educated young black journalist, brought him back to activism and prominence. Shortly thereafter, in 1884, he married Helen Pitts, daughter of his white abolitionist friend Gideon Pitts. She was an activist in women’s rights and in abolition, and had taught at the Hampton Institute, then moved in 1880 to Washington. There she was co-editor of The Alpha, a feminist publication, was hired by Douglass to work as a clerk in his office of the Recorder of Deeds, and had moved next door to Frederick and Anna in Anacostia.

Their marriage, of course, was resisted in many quarters, including among Douglass’ four living children, and Helen’s parents; though they were supported by mutual friend, abolitionist and women’s rights advocate Elizabeth Cady Stanton. They were married for eleven years, during which time they traveled to numerous places, including Europe and Africa; Douglass served his appointments to Haiti and the Dominican Republic, and he continued to make many public speeches.

On February 20, 1895, Douglass attended a meeting of the National Council of Women in Washington and received a standing ovation. He suffered a massive heart failure after he returned home to Cedar Hill, and died. He had bequeathed the house to Helen, but because of the lack of sufficient signatures on his will, she had to purchase the house from her co-heirs, his children, and she spent the rest of her life working to memorialize him with the house and the Frederick Douglass Memorial and Historical Association, which she established. Upon her death, the mortgage was paid by, and the house was bought by The National Association of Colored Women, who maintained it until it was acquired by the National Park Service in 1962.

|

|

|

|

Please consider Donating to the Frederick Douglass Honor Society |

|

FOR CURRENT INFORMATION PLEASE FOLLOW US ON FACEBOOK |

| |

| HOME • EVENTS • SCHOLARSHIP • CONTRIBUTE • MERCHANDISE • VIDEOS • DOUGLASS HISTORY • DOUGLASS WRITINGS • CONTACT |

| |

| ©2024 Frederick Douglass Honor Society, All Rights Reserved. |

|