The Writings of Frederick Douglass

A Call to Work

November 19, 1852

(From the Frederick Douglass’ Paper)

The mission of the political abolitionists of this country is to abolish slavery. The means to accomplish this great end is, first, to disseminate antislavery sentiment; and, secondly, to combine that sentiment and render it a political force which shall, for a time, operate as a check on violent measures for supporting slavery; and, finally, overthrow the great evil of slavery itself.—The end sought is sanctioned by God and all his holy angels, by every principle of justice, by every pulsation of humanity, and by all the hopes of this republic. A better cause never summoned men to its support, nor invoked the blessings of heaven for success. Its opponents (whether they know it or not) are fighting against all that is noble in man—all that is best in society; and if their principles shall prove uneradicable, and their measures successful, then, just so sure as there is a God in the universe, the hope of this republic will go out in blood. Men may laugh— they may scoff—they may wrap themselves in heedless indifference; but every fact of history, every sentiment of religion, every indication of Providence proclaims, trumpet-tongued, that a day of reckoning will come. If this guilty country be saved—if it be made a blessing to mankind, that result will be accomplished, under God, by the faithful and self-sacrificing labors of the abolitionists. The work is great—very great. There has been a great deal done; but there is much more to do. There never was a time when we should advance to that work with a lighter heart or a firmer tread. The anti-slavery sentiment of the country has just made its mark on the public records in a manner not to be despised, and well calculated to inspire confidence in final success. The means are at hand to carry that mark higher still. Whoever lives to see the year 1856, will see anti-slavery in the field, with a broader front and loftier mien than it ever wore before.

Causes are in operation greatly calculated to concentrate the anti-slavery sentiment, and to bring it to bear directly against slavery. One of these causes is the complete overthrow of the Whig party, and the necessity which it imposes upon its Northern anti-slavery members to assume an attitude more in harmony with their convictions than they could do on the Baltimore platform. The Southern wing of this party (never very reliable) will naturally become fused into the Democratic party, with which it is now more in sympathy than it can be with Northern Whigs. It is evident, that the Whigs of the North must stand alone or stand with us. It is equally evident that they cannot, and do not, desire to array themselves against the only living sentiment of the North, since they would, by such a course, only commit political suicide and make themselves of no political consequence. The danger now to be apprehended is, not that our numbers will not increase, and increase rapidly and largely, but that we shall be tempted to modify our platform of principles and abate the stringency of our testimonies, so as to accommodate the wishes of those who have not hitherto distinctly acted with us, and who now wish to do so.

Now the way to swell our vote for freedom and to prevent the evil, thus briefly hinted at, is, to spread anti-slavery light, and to educate the people on the whole subject of slavery—circulate the documents—let the anti-slavery speaker, more than ever, go abroad—let every town be visited, and let truth find its way into every house in the land. The people want to do what is best. They must be shown that to do right is best. The great work to be done is to educate the people, and to this work the abolitionist should address himself with full purpose of heart.—This is no time for rest; but a time for every one to be up and doing. The battle, though not just begun, is far from being completed. The friends of freedom, in their various towns and counties, should, without waiting for some central organization to move in the matter, take up the work themselves—collect funds—form committees—send for documents— call in lecturers, and bring the great question of the day distinctly and fully before their fellow-citizens. We would not give the snap of our finger for one who begins and ends his anti-slavery labors on election day. Anti-slavery papers are to be upheld—lecturers are to be sustained—correspondence is to be kept up— acquaintances are to be formed with those who sympathize with us, and a fraternal and brotherly feeling is to be increased, strengthened and kept up. Here, then, is work—work for every one to do—work which must be done if ever the great cause in which we have embarked is brought to a happy consummation. Let every one make this cause his own. Let him remember the deeply injured and imbruted slave as bound with him. Let him not forget that he is but a steward, and that he is bound to make a righteous use of his Lord’s money. Let him make his anti-slavery a part of his very being, and God will bless him and increase him an hundred fold. Now is the time for a real anti-slavery revival. The efforts to silence discussion should be rebuked. We ought not, we must not be “hushed and mum” at the bidding of slave power conventions, or any other power on earth.

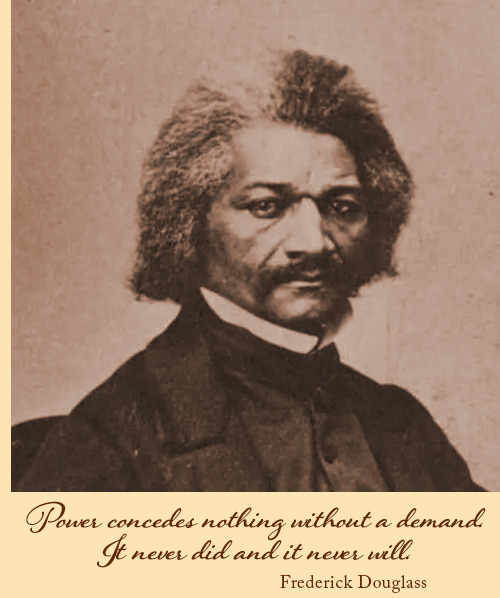

Frederick Douglass was one of the most prolific writers os the 19th century. He wrote three autobiographies, each one expanding on the details of his life. The first was Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written By Himself (1845); the second was My Bondage and My Freedom (1855); and the third was Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881). They are now foremost examples of the American slave narrative. After escaping from slavery, Douglass began giving speeches about his life and experiences. His first autobiography brought him fame throughout the United States and the United Kingdom. Douglass founded his first paper, the North Star. He served as its chief editor and authored a considerable body of letters, editorials, and speeches from then on.

We present a number of his writings here and will add more over time. His writings have been collected in many volumes and many are also available on the Library of Congress website.

The Church and Prejudice

- November 4, 1841

Farewell Speech to the British People - March 30, 1847

What to the Slave is the Fourth of July? - July 5, 1852

A Call To Work - November 19, 1852