The Writings of Frederick Douglass

Farewell Speech to the British People

March 30, 1847

(Delivered at the Valedictory Soiree given to him at the London Tavern, London, England.)

Mr. Chairman, Ladies and Gentlemen:

I never appear before an audience like that which I now behold, without feeling my incompetency to do justice to the cause which I am here to advocate, or to meet the expectations which are generally created for me, by the friends who usually precede me in speaking. Certainly, if the eulogiums bestowed upon me this evening were correct, I should be able to chain the attention of this audience for hours by my eloquence. But, sir, I claim none of these qualities. While I feel grateful for the generosity of my friends in bestowing them upon me, I am conscious of possessing very little just right to them; for I am but a plain, blunt man— a poor slave, or, rather, one who has been a slave. [Cheers.] Never had I a day’s schooling in my life; all that I have of education I have stolen. [Laughter.] I am desirous, therefore, at once to relieve you from any anticipation of a great speech, which, from what you have heard from our esteemed friend, the chairman, and the gentlemen who preceded me, you might have been led to expect. That I am deeply, earnestly, and devotedly engaged in advocating the cause of my oppressed brethren, is most true; and in that character, as their representative, I hail your kind expression of feeling towards me this evening, and receive it with the profoundest gratitude. I will make use of these demonstrations of your warm approbation hereafter; I will take them home in my memory; they shall be written upon my heart; and I will employ them in that land of boasted liberty and light, but, at the same time, of abject slavery, to which I am going, for the purpose of overthrowing that accursed system of bondage, and restoring the Negroes, throughout its wide domain, to their lost liberty and rights. Sir, the time for argument upon this question is over, so far as the right of the slave to himself is concerned; and hence I feel less freedom in speaking here this evening, than I should have done under other circumstances. Place me in the midst of a pro-slavery mob in the United States, where my rights as a man are cloven down—let me be in an assembly of ministers or politicians who call in question my claim to freedom—and then, indeed, I can stand up and open my month; then assert boldly and strongly the rights of my manhood. [Cheers.] But where all is admitted—where almost every man is waiting for the end of a sentence that he may respond to it with a cheer—listening for the last words of the most radical resolution that he may hold up his hand in favour of it—why, then, under such circumstances, I certainly have very little to do. You have done all for me. Still, sir, I may manage, out of the scraps of the cloth which you have left, to make a coat of many colours, not such an one as Joseph was clothed in, yet still bearing some resemblance to it. I do not, however, promise to make you a very connected speech. I have listened to the patriotic, or rather respectful, language applied to America and Americans this evening. I confess, that although I am going back to that country, though I have many dear friends there, though I expect to end my days upon its soil, I am, nevertheless, not here to make any profession whatever of respect for that country, of attachment to its politicians, or love for its churches or national institutions. The fact is, the whole system, the entire network of American society, is one great falsehood, from beginning to end. I might say, that the present generation of Americans have become dishonest men from the circumstances by which they are surrounded. Seventy years ago, they went to the battle-field in defence of liberty. Sixty years ago, they framed a constitution, over the very gateway of which they inscribed, “To secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and posterity.” In their celebrated Declaration of Independence, they made the loudest and clearest assertions of the rights of man; and yet at that very time the identical men who drew up that Declaration of Independence, and framed the American democratic constitution, were trafficking in the blood and souls of their fellow men. [Hear, hear.] From the period of the first adoption of the constitution of the United States downward, everything good and great in the heart of the American people— everything patriotic within their breasts—has been summoned to defend this great lie before the world. They have been driven from their very patriotism, to defend this great falsehood. How have they done it? Why, by wrapping it up in honeyed words. [Hear.] By disguising it, and calling it “our peculiar institution;” “our social system;” “our patriarchal institution;” “our domestic institution;” and so forth. They have spoken of it in every possible way, except the right way. In no less than three clauses of their constitution may be found a spirit of the most deadly hostility to the liberty of the black man in that country, and yet clothed in such language as no Englishman, to whom its meaning was unknown, could take offence at. For instance, the President of the United States is required, at all times and under any circumstances, to call out the army and navy to suppress “domestic insurrection.” Of course, all Englishmen, upon a superficial reading of that clause of the constitution, would very readily assent to the justice of the proposition involved in it; they would agree at once in its perfect propriety. “The army and navy! what are they good for if not to suppress insurrections, and preserve the peace, tranquillity, and harmony of the state?” But what does this language really mean, sir? What is its signification, as shadowed forth practically, in that constitution? What is the idea it conveys to the mind of the American? Why, that every man who casts a ball into the American ballot-box—every man who pledges himself to raise his hand in support of the American constitution—every individual who swears to support this instrument—at the same time swears that the slaves of that country shall either remain slaves or die. [Hear, hear.] This clause of the constitution, in fact, converts every white American into an enemy to the black man in that land of professed liberty. Every bayonet, sword, musket, and cannon has its deadly aim at the bosom of the Negro: 3,000,000 of the coloured race are lying there under the heels of 17,000,000 of their white fellow creatures.

There they stand, with all their education, with all their religion, with all their moral influence, with all their means of co-operation—there they stand, sworn before God and the universe, that the slave shall continue a slave or die. [Hear, hear, and cries of “Shame.”] Then, take another clause of the American constitution. “No person held to service or labour, in any state within the limits thereof, escaping into another, shall in consequence of any law or regulation therein, be released from such service or labour, but shall be delivered up to be claimed by the party to whom such service or labour may be due.” Upon the face of this clause there is nothing of injustice or inhumanity in it. It appears perfectly in accordance with justice, and in every respect humane. It is, indeed, just what it should be, according to your English notion of things and the general use of words. But what does it mean in the United States? I will tell you what it signifies there—that if any slave, in the darkness of midnight, looks down upon himself, feeling his limbs and thinking himself a man, and entitled to the rights of a man, shall steal away from his hovel or quarter, snap the chain that bound his leg, break the fetter that linked him to slavery, and seek refuge from the free institutions of a democracy, within the boundary of a monarchy, that that slave, in all his windings by night and by day, in his way from the land of slavery to the abode of freedom, shall be liable to be hunted down like a felon, and dragged back to the hopeless bondage from which he was endeavouring to escape. So that this clause of the constitution is one of the most effective safeguards of that slave system of which we have met here this evening to express our detestation. This clause of the American constitution makes the whole land one vast hunting- ground for men: it gives to the slaveholder the right at any moment to set his well-trained bloodhounds upon the track of the poor fugitive; hunt him down like a wild beast, and hurl him back to the jaws of slavery, from which he had, for a brief space of time, escaped. This clause of the constitution consecrates every rood of earth in that land over which the star-spangled banner waves as slave-hunting ground. Sir, there is no valley so deep, no mountain so high, no plain so expansive, no spot so sacred, throughout the length and breadth of America, as to enable a man, not having a skin coloured like your own, to enjoy the free and unrestrained right to his own hands. If he attempt to assert such a right he may be hunted down in a moment. Sir, in the Mosaic economy, to which reference has been made this evening by a preceding speaker, we have a command given, as it were, amid the thunders and lightnings from Sinai, “Thou shalt not deliver unto his master the servant that is escaped unto thee: he shall dwell with thee in the place that liketh him best: thou shalt not oppress him!” America, religious America, has run into the very face of Jehovah, and said, “Thou shalt deliver him unto his master.” [Hear, hear.] “Thou shalt deliver unto the tyrant, who usurps authority over his fellow man, the trembling bondman that escapes into your midst.” Sir, this clause of the American constitution is one of the most deadly enactments against the natural rights of man: above and beyond all its other provisions, it serves to keep up that system of fraud, wrong, and inhumanity which is now crushing 3,000,000 of human beings identified with me in their complexion, and formerly in their chains. How is it? Why, the slaveholders of the South would be wholly unable to hold their slaves were it not for the existence of the protection afforded by this constitution; but for this the slaves would run away. No, no; they do not love their masters so well as the tyrants sometimes flatter themselves; they do frequently run away. You have an instance of their disposition to run away before you. [Loud cheers.]

Why, sir, the Northern States claim to be exempt from all responsibility in the matter of the slaveholding of America, because they do not actually hold slaves themselves upon their own soil. But this is a mere subterfuge. What is the actual position of those Northern States? If they are not actual slaveholders, they stand around the slave system and support it. They say to the slaveholder, “We have a sentiment against—we have a feeling opposed to—we have an abhorrence of— slavery. We would not hold slaves ourselves, and we are most sincerely opposed to slavery; but, still, if your Negroes run away from you to us, we will return them to you. And, while you can make the slaves believe that we will so return them, why, of course, they will not run away into our states: and, then, if they should attempt to gain their freedom by force, why, we will bring down upon them the whole civil, military, and naval power of the nation and crush them again into subjection. While we make them believe that we will do this, we give them the most complete evidence that we will, by our votes in congress and in the senate, by our religious assemblies, our synods, presbyteries and conferences, by our individual votes, by our deadly hate and deep prejudice against the coloured man, even when he is free, we will, by all these evidences, give you the means of convincing the slave, that, if he does attempt to gain his freedom, we will kill him. But still, notwithstanding all this, let it be clearly understood that we hate slavery.” [Laughter and cheers.] This is the guilty position even of those who do not themselves hold slaves in America. And, under such circumstances, I really cannot be very patriotic when speaking of their national institutions and boasted constitution, and, therefore, I hope you will not expect any very eloquent outbursts of eulogy or praise of America from me upon the present occasion. [Loud cheers.] No, my friends; I am going back, determined to be honest with America. I am going to the United States in a few days, but I go there to do, as I have done here, to unmask her pretensions to republicanism, and expose her hypocritical professions of Christianity; to denounce her high claims to civilisation, and proclaim in her ears the wrongs of those who cry day and night to Heaven, “How long! how long! O Lord God of Sabaoth!” [Loud cheers.] I go to that land, not to foster her national pride, or utter fulsome words about her greatness. She is great in territory; great in numerical strength; great in intellectual sagacity; great in her enterprise and industry. She may boast of her broad lakes and mighty rivers; but, sir, while I remember, that with her broadest lakes and finest rivers, the tears and blood of my brethren are mingled and forgotten, I cannot speak well of her; I cannot be loud in her praise, or pour forth warm eulogiums upon her name or institutions. [Cheers.] No; she is unworthy of the name of great or free. She stands upon the quivering heartstrings of 3,000,000 of people. She punishes the black man for crimes, for which she allows the white man to escape. She declares in her statute-book, that the black man shall be seventy times more liable to the punishment of death than the white man. In the state of Virginia, there are seventy-one crimes for which a black man may be punished with death, only one of which crimes will bring upon the white man a like punishment. [Hear, hear.] She will not allow her black population to meet together and worship God according to the dictates of their own consciences. If they assemble together more than seven in number for the purpose of worshipping God, or improving their minds in any way, shape, or form, each one of them may legally be taken and whipped with thirty-nine lashes upon his bare back. If any one of them shall be found riding a horse, by day or by night, he may be taken and whipped forty lashes on his naked back, have his ears cropped, and his cheek branded with a red-hot iron. In all the slave states south, they make it a crime punishable with severe fines, and imprisonment in many cases, to teach or instruct a slave to read the pages of Inspired Wisdom. In the state of Mississippi, a man is liable to a heavy fine for teaching a slave to read. In the state of Alabama, for the third offence, it is death to teach a slave to read. In the state of Louisiana, for the second offence, it is death to teach a slave to read. In the state of South Carolina, for the third offence of teaching a slave to read, it is death by the law. To aid a slave in escaping from a brutal owner, no matter how inhuman the treatment he may have received at the hands of his tyrannical master, it is death by the law. For a woman, in defence of her own person and dignity, against the brutal and infernal designs of a determined master, to raise her hand in protection of her chastity, may legally subject her to be put to death upon the spot. [Loud cries of “Shame, shame.”] Sir, I cannot speak of such a nation as this with any degree of complacency, [cheers], and more especially when that very nation is loud and long in its boasts of holy liberty and light; when, upon the wings of the press, she is hurling her denunciations at the despotisms of Europe, when she is embracing every opportunity to scorn and scoff at the English government, and taunt and denounce her people as a community of slaves, bowing under a haughty monarchy; when she has stamped upon her coin, from the cent to the dollar, from the dollar to the eagle, the sacred name of liberty; when upon every hill may be seen erected, a pole, bearing the cap of liberty, under which waves the star-spangled banner; when, upon every 4th of July, we hear declarations like this: “O God! we thank Thee that we live in a land of religious and civil liberty!” when from every platform, upon that day, we hear orators rise and say:—

Ours is a glorious land;

Her broad-arms stretch from shore to shore,

The broad Pacific chafes her strand,

She hears the dark Atlantic roar;

Enamelled on her ample breast,

A many a goodly prospect stands.

Ours is the land of the free and the home of the brave.

I say, when professions like these are put forth vauntingly before the world, and I remember the scenes I have witnessed in, and the facts I know, respecting that country, why, then, let others do as they will, I have no word of patriotic applause for America or her institutions. [Enthusiastic and protracted cheering.] America presents to the world an anomaly, such as no other nation ever did or can present before mankind. The people of the United States are the boldest in their pretensions to freedom, and the loudest in their profession of love of liberty; yet no nation upon the face of the globe can exhibit a statute-book so full of all that is cruel, malicious, and infernal, as the American code of laws. Every page is red with the blood of the American slave. O’Connell once said, speaking of Ireland—no matter for my illustration, how truly or falsely—that “her history may be traced, like the track of a wounded man through a crowd.” If this description can be given of Ireland, how much more true is it when applied to the sons and daughters of Africa, in the United States? Their history is nothing but blood! blood!—blood in the morning, blood at noon, blood at night! They have had blood to drink; they have had their own blood shed. At this moment we may exclaim

What, ho! our countrymen in chains!

The whip on woman’s shrinking flesh!

Our soil still redd’ning with the stains

Caught from her scourging, warm and fresh!

What! mothers from their children riven!

What! God’s own image bought and sold!

Americans to market driven,

And barter’d, as the brutes, for gold!

And this, too, sir, in the midst of a people professing, not merely republicanism, not merely democratical institutions, but civilisation; nay, more—Christianity, in its highest, purest, and broadest sense [hear, hear]; claiming to be the heaven- appointed nation, in connexion with the British, to civilise, christianise, and evangelise the world. For this purpose, sir, we have our Tract, Bible, and Missionary Societies; our Sabbath-school and Education Societies; we have in array all these manifestations of religious life, and yet, in the midst of them all—amid the eloquence of the orators who swagger at all these meetings—may be heard the clanking of the fetter, the rattling of the chain, and the crack of the slave- driver’s whip. The very man who ascends the platform, and is greeted with rounds of applause when he comes forward to speak on the subject of extending the victories of the cross of Christ, “from the rivers to the ends of the earth,” has actually come to that missionary meeting with money red with the blood of the slave; with gold dripping with gore from the plantations. The very man who stands up there—Dr. Plummer, for instance, Dr. Marsh, Dr. Anderson, Dr. Cooper, or some other such doctor—comes to the missionary meeting for the purpose of promoting Christianity, Evangelical Christianity, with the price of blood in his possession. He stands up and preaches with it in his pocket, and gives it to aid the holy cause of sending missionaries to heathen lands. This is the spectacle we witness annually at New York and Philadelphia; and sometimes they have the temerity to come as far as Boston with their blood-stained money. We are a nation of inconsistencies; completely made up of inconsistencies. Mr. John C. Calhoun, the great Southern statesman of the United States, is regarded in that country as a real democrat, “dyed in the wool,” “a right out-and-out democrat,” “a back-bone democrat.” By these and similar phrases they speak of him; and yet, sir, that very man stands upon the floor of the senate, and actually boasts that he is a robber! that he is an owner of slaves in the Southern states. He positively makes his boast of this disgraceful fact, and assigns it as a reason why he should be listened to as a man of consequence—a person of great importance. All his pretensions are founded upon the fact of his being a slaveowner. The audacity of these men is actually astounding; I scarcely know what to say in America, when I hear men deliberately get up and assert a right to property in my limbs—my very body and soul; that they have a right to me! that / am in their hands, “a chattel personal to all intents, purposes, and constructions whatsoever;” “a thing” to be bought and sold!—to be sure, having moral perceptions; certainly possessing intellect, and a sense of my own rights, and endowed with resolution to assert them whenever an opportunity occurred; and yet, notwithstanding, a slave! a marketable commodity! I do not know what to think of these men; I hardly know how to answer them when they speak in this manner. And, yet, this self-same John C. Calhoun, while he vehemently declaims for liberty, and asserts that any attempt to abridge the rights of the people should be met with the sternest resistance on all hands, deliberately stands forth at the head of the democracy of that country and talks of his right to property in me; and not only in my body, but in the bodies and souls of hundreds and thousands of others in the United States. As with this honorable gentleman, so is it with the doctors of divinity in America; for, after all, slavery finds no defenders there so formidable as them. They are more skilful, adroit, and persevering, and will descend even to greater meannesses, than any other class of opponents with whom the abolitionists have to contend in that country. The church in America is, beyond all question, the chief refuge of slavery. When we attack it in the state, it runs into the street, to the mob; when we attack it in the mob, it flies to the church; and, sir, it is a melancholy fact, that it finds a better, safer, and more secure protection from the shafts of abolitionism within the sacred enclosure of the Christian temple than from any other quarter whatever. [Hear, hear.] Slavery finds no champions so bold, brave, and uncompromising as the ministers of religion. These men come forth, clad in all the sanctity of the pastoral office, and enforce slavery with the Bible in their hands, and under the awful name of the Everlasting God. We there find them preaching sermon after sermon in support of the system of slavery as an institution consistent with the Gospel of Jesus Christ. We have commentary after commentary attempting to wrest the sacred pages of the Bible into a justification of the iniquitous system. And, sir, this may explain to you what might otherwise appear unaccountable in regard to the conduct and proceedings of American abolitionists. I am very desirous of saying a word or two on this point, upon which there has been much misrepresentation. I say, the fact that slavery takes refuge in the churches of the United States will explain to you another fact, which is, that the opponents of slavery in America are almost universally branded there—and, I am sorry to say, to some extent in this country also—as infidels. [Loud cries of “Shame, shame.”] Why is this?

Simply because slavery is sheltered by the church. The warfare in favour of emancipation in America is a very different thing from the warfare which you had to wage on behalf of freedom in the West India Islands. On that occasion, thank God! religion was in its right position, and slavery in its proper place—in fierce antagonism to each other. Religion and slavery were then the enemies of each other. Slavery hated Religion with the utmost intensity; it pursued the missionary with the greatest malignity, burning down his chapel, mobbing his house, jeopardising his life, and rendering his property utterly insecure. There was an antipathy deep and lasting between slavery and the exponents of Christianity in the West India Islands. All honour to the names of Knibb and Burchell! [Loud cheers.] Those men were indeed found faithful to Him who commanded them to “Preach deliverance to the captive, and the opening of the prison to them that were bound.” [Loud cheers.] But, sir, the natural consequence of such faithfulness was, that these men were hated with the most deadly hate by the slave- owners, who with their abettors, used every effort to crush that living voice of truth coming from the bosom of the Christian church, which was endeavouring to dash down the bloody altars of slavery, and scatter its guilty profits to the winds. Slavery was opposed by the church in the West Indies: not so in America; there, religion and slavery are linked and interlinked with each other—woven and interwoven together. In the United States we have slaveholders as class-leaders, ministers of the Gospel, elders, deacons, doctors of divinity, professors of theology, and even bishops. We have the slaveholder in all parts of the church. Wherever he is, he is an active, energetic, vigilant man. Slavery never sleeps or slumbers. The slaveholder who goes to his bed for the purpose of taking rest does not pass his night in tranquillity and peace; but, knowing his danger, he takes his pistol, bowie-knife, and dirk with him. He is uneasy; he is aware that he lies upon bleeding heartstrings, that he sleeps upon the wretchedness of men, that he rests himself upon the quivering flesh of his fellow creatures around him; he is conscious that there is intellect burning—a spark of divinity enkindled—within the bosoms of the men he oppresses, who are watching for, and will seize upon, the first opportunity to burst their bonds asunder, and mete out justice to the wretch who has doomed them to slavery. [Loud cheers.] The slaveowner, therefore, is compelled to be watchful; he cannot sleep; there is a morbid sensitiveness in his breast upon this subject: everything that looks like opposition to slavery is promptly met by him and put down. Whatever, either in the church or the state, may appear to have a tendency to undermine, sap, or destroy the foundation of slavery is instantly grappled with; and, by their religion, their energy, their perseverance, their unity of feeling, and identity of interest, the slaveholder and the church have ever had the power to command a majority to put down any efforts for the emancipation of the coloured race, and to sustain slavery in all its horrors. Thus has slavery been protected and sheltered by the church. Slavery has not only framed our civil and criminal code, it has not only nominated our presidents, judges, and diplomatic agents, but it has also given to us the most popular commentators on the Bible in America. [Hear, hear.] It has given to us our religion, shaped our morality, and fashioned it favourable to its own existence. Thus is it that slavery is ensconced at this moment; and, when the abolitionist sees slavery thus woven and interwoven with the very texture—with the whole network—of our social and religious organizations, why he resolves, at whatever hazard of reputation, ease, comfort, luxury, or even of life itself, to pursue, and, if possible, destroy it. [Loud cheers.] Sir, to illustrate our principle of action, I might say that we adopt the motto of Pat, upon entering a Tipperary row. Said he, “Wherever you see a head, hit it!” [Loud cheers and laughter.] Sir, the abolitionists have resolved, that wherever slavery manifests itself in the United States, they will hit it. [Renewed cheering.] They will deal out their heaviest blows upon it. Hence, having followed it from the state to the street, from the mob to the church, from the church to the pulpit, they are now hunting it down there. But slavery in the present day affects to be very pious; it is uncommonly devotional, all at once. It feels disposed to pray the very moment you touch it. The hideous fiend kneels down and pretends to engage in devotional exercises; and when we come to attack it, it howls piously—”Off! you are an infidel”; and straightway the press in America, and some portion of the press in this land also, take up the false cry. [Hear, hear.] Forthwith a clamour is got up here, not against the slaveholder, but against the man who is virtuously labouring for the overthrow of that which his assailants profess to hate—slavery. [Loud cheers.] A fierce outcry is raised, not in favour of the slave, but against him and against his best and only friends. Sir, when the history of the emancipation movement shall have been fairly written, it will be found that the abolitionists of the nineteenth century were the only men who dared to defend the Bible from the blasphemous charge of sanctioning and sanctifying Negro slavery. [Loud cheers.] It will be found that they were the only men who dared to stand up and demand, that the churches calling themselves by the name of Christ, should entirely, and for ever, purify themselves from all contact, connection, and fellowship with men who gain their fortunes by the blood of souls. It will be found that they were the men who “cried aloud and spared not;” who “lifted their voices like trumpets,” against the giant iniquity by which they were surrounded. It will then be seen that they were the men who planted themselves on the immutable, eternal, and all-comprehensive principle of the sacred New Testament—”All things whatsoever ye would that men should do unto you, do ye even so unto them”—that, acting on this principle, and feeling that if the fetters were on their own limbs, the chain upon their own persons, the lash falling quick and hard upon their own quivering bodies, they would desire their fellow men about them to be faithful to their cause; and, therefore, carrying out this principle, they have dared to risk their lives, fortunes, nay, their all, for the purpose of rescuing from the tyrannous grasp of the slaveholder these 3,000,000 of trampled-down children of men. [Loud cheers.]

Sir, the foremost, strongest, and mightiest among those who have completely identified themselves with the Negroes in the United States, I will now name here; and I do so because his name has been most unjustly coupled with odium in this country. [Hear, hear.] I will name, if only as an expression of gratitude on my part, my beloved, esteemed, and almost venerated friend, William Lloyd Garrison. [Loud and prolonged cheering.] Sir, I have now been in this country for nineteen months; I have gone through its length and breadth; I have had sympathy here and sympathy there; co-operation here, and co-operation there; in fact, I have scarcely met a man who has withheld fellowship from me as an abolitionist, standing unconnected with William Lloyd Garrison. [Hear.] Had I stood disconnected from that great and good man, then numerous and influential parties would have held out to me the right hand of fellowship, sanctioned my proceedings in England, backed me up with money and praise, and have given me a great reputation, so far as they were capable; and they were men of influence. And why, sir, is William Lloyd Garrison hated and despised by certain parties in this country? What has he done to deserve such treatment at their hands? He has done that which all great reformers and pioneers in the cause of freedom or religion have ever been called upon to do—made himself unpopular for life in the maintenance of great principles. He has thrown himself, as it were, over the ditch as a bridge; his own body, his personal reputation, his individual property, his wide and giant- hearted intellect, all were sacrificed to form a bridge that others might pass over and enjoy a rich reward from the labours that he had bestowed, and the seed which he had sown. He has made himself disreputable. How? By his uncompromising hostility to slavery, by his bold, scathing denunciation of tyranny; his unwavering, inflexible adherence to principle; and by his frank, open, determined spirit of opposition to everything like cant and hypocrisy. [Loud cheers.] Such is the position in which he stands among the American people. And the same feeling exists in this country to a great extent. Because William Lloyd Garrison has upon both sides of the Atlantic fearlessly unmasked hypocrisy, and branded impiety in language in which impiety deserves to be characterized, he has thereby brought down upon himself the fierce execrations of a religious party in this land. But, sir, I do not like, upon the present occasion, even to allude to this subject; for the party who have acted in this manner is small and insignificant; so impotent for good, so well known for its recklessness of statement, so proverbial for harshness of spirit, that I will not dwell any longer on their conduct. I feel that I ought not to trespass upon your patience any further. [Loud cheers and cries of “Go on, go on.”] Well, then, as you are so indulgent to me, I will refer to another matter. It would not be right and proper, from any consideration of regard and esteem which I feel for those who have honoured me by assembling here this evening to bid me farewell—especially to some who have honoured me and the cause I am identified with, honoured themselves and our common humanity, by being present to-night upon this platform—I say it would not be proper in me, out of deference to any such persons, on this occasion, to fail to advert to what I deem one of the greatest sins of omission ever committed by British Christians in this country. I allude to the recent meeting of the Ecumenical Evangelical Alliance. [Hear.] Sir, I must be permitted to say a word or two upon this matter. [Hear.] From my very love to British Christians—out of esteem for the very motives of those excellent men who composed the British part of that great convention—from all these considerations, I am bound to state here my firm belief, that they suffered themselves to be sadly hoodwinked upon this point. [Hear, hear.] They were misled and cajoled into a position on this question, which no subsequent action can completely obliterate or entirely atone for. They had it in their power to have given slavery a blow which would have sent it reeling to its grave, as if smitten by a voice or an arm from Heaven. They had moral power; they had more—they had religious power. They were in a position which no other body ever occupied, and in which no other association will ever stand, while slavery exists in the United States. [Hear.] They were raised up on a pinnacle of great eminence: they were “a city set on a hill.” They were a body to whom the whole evangelical world was looking, during that memorable month of August. Pressed down deep among evangelical Christians, under the feet of some there, were 3,000,000 of slaves looking to the Evangelical Alliance, with uplifted hands, with imploring tones— or, rather, I should say in the absence of tones, for the slave is dead; he has no voice in such assemblies; he can send no delegates to Bible and Missionary Societies, Temperance Conventions, or Evangelican Alliances; he is not permitted to send representatives there to tell his wrongs. He has his pressing evils and deeply aggravated wrongs, to which he is constantly subject; but he is not allowed to depute any voice to plead his cause. Still, in the silence of annihilation—of mental and moral annihilation—in the very eloquence of extinction, he cried to the Evangelical Alliance to utter a word on behalf of his freedom. They “passed him by on the other side.” [Loud cheers.] Sir, I am sorry for this, deeply sorry; sorry on their own account, for I know they are not satisfied with their position. I am sorry that they should, from a timidity on their part—a fear of offending those who were called “The American brethren “—have given themselves the pain and trouble to repent on this question. But still, I hope they will repent; and I believe that many of them have already repented [hear, hear]; I believe that those who were hoodwinked on that occasion, when they shall be brought to see that they were miserably deceived—misled by the jack o’ lanterns from America, [laughter]—that they will add another element to their former opposition to slavery, and that is, the pain and sense of injustice done to themselves on the part of the American delegates. From the very feeling of having been betrayed into a wrong position, they will feel bound to deal a sharp, powerful, and pungent rebuke to those guilty men who dared to lead them astray. Sir, after all, I do not wonder at the manner in which the British delegates were deluded; when I reflect upon the subtlety of the Americans, their apparently open, free, frank, candid, and unsophisticated disposition—how they stood up and declared to the British brethren that they were honest, and looked so honestly, and smiled so blandly at the same time. No; I do not wonder at their success, when I think how old and skilful they are in the practice of misrepresentation—in the art of lying. [Hear.] Coarse as the expression I have here applied to them may be, Mr. Chairman, it is, nevertheless, true; the thing exists. If I am branded for coarseness on the present occasion, I must excuse myself by telling you I have a coarse thing and a foul business to lay before you. As with the president, so with these deputations from America; there is not a single inaugural speech, not an annual message, but teems with lies like this—that “in this land every man enjoys the protection of the law, the protection of his property, the protection of his person, the protection of his liberty.” They iterate and reiterate these statements over and over again. Thus, these Americans, as I said before, are skilled in the art of falsehood. I do not wonder at their success, when I recollect that they brought religion to aid them in their fraud; for they not only told their falsehood with the blandness, oratory, and smiling looks of the politicians in their own country, but they combined with those seductive qualities a loud profession of piety; and in this way they have succeeded well in misleading the judgments of some of the most intrepid, bright, and illustrious of slavery’s foes in the ranks of the ministers of religion of England. [Hear.] Among the arguments used at the meeting of the Evangelical Alliance, the following stood preeminent: “You, British ministers, should not interfere with slavery, or pass resolutions to exclude slaveholders from your fellowship, because,” it was cooly said, “the slaveholders are placed in difficult circumstances.” It was stated that the slaveholders could not get rid of their slaves if they wished; that they were anxiously desirous of emancipating their slaves, but that the laws of the states in which they lived were such as to compel them to hold them whether they would or not. It was alleged that their peculiar circumstances make it a matter of Christian duty in them to hold their slaves.

Sir, I know the stubborn and dogged manner in which these statements were made; and I am conscious how well calculated they were to excite sympathy for the slaveholders: but I am here to tell you, that there was not one word of truth in any of these plausible assertions. There was, indeed, a slight shadow of light; a glimmering might be detected by an argus eye, but not certainly by the eye of man. There was a faint semblance of truth in it; a slight shadow; but, after all, it was only a semblance. [Hear.] What are the facts of the case? Just these: that in three or four of the Southern states, when a man emancipates his slaves, he is obliged to give a bond that such slaves shall not become chargeable to the state as paupers. That is all the “impediment;” that is the whole of the “difficulty” as regards the law. But the fact is, that the free Negroes never become paupers. I do not know that I ever saw a black pauper. The free Negroes in Philadelphia, 25,000 in number, not only support their own poor, by their own benevolent societies, but actually pay 500 dollars per annum for the support of the white paupers in the state. [Loud cheers.] No, sir, the statement is false; we do not have black paupers in America; we leave pauperism to be fostered and taken care of by white people; not that I intend any disrespect to my audience in making this statement. [Hear.] I can assure you I am in nowise prejudiced against colour. [Laughter.] But the idea of a black pauper in the United States is most absurd. But, after all, what does the objection amount to? What if really they have to give a bond to the State that the slaves whom they emancipate should not become chargeable to the state? Why, sir, one would think this would be a very little matter of consideration to a just and Christian man; considering that all the wealth that this conscientious slave-holder possesses, he has wrung from the unrequited toil of the slave. It is not much, when it is recollected that he kept the poor Negro in ignorance, and worked him twenty-eight or thirty years of his life, and that he has had the fruit of his labour during the best part of his days. But yet, it is gravely stated, that the slave-owner looks on it as a great hardship, that if he emancipates his slave he is bound not to suffer him to become chargeable to the state. Why, the money which the slave should have earned in his youthful days, to support him in the season of age, has been wrung from him by his Christian master. But the slaveholder of America had no occasion ever to have had such a difficulty as this to contend with before he gets rid of his slave. I may mention a fact, which is not generally known here, that this law was adopted in the slave states—for what purpose? I will tell you why: because it was previously the custom of a large class of slaveholders to hold their slaves in bondage from infancy to old age, so long as they could toil and struggle and were worth a penny a day to their masters. While they could do this, they were kept; but, as soon as they became old and decrepit—the moment they were unable to toil—their masters, from very benevolence and humanity of course, gave them their freedom. [Hear, hear.] The inhabitants of the states, to prevent this burden upon their community, made the masters liable for their support under such circumstances. Dr. Cox did not tell you that in his famous speech in the Evangelical Alliance. [Hear, hear.] I mean Dr. Cox of America. (Mr. Douglass here turned to Dr. Cox of Hackney, which caused much laughter.) I do rejoice that there is another Dr. Cox in the world, of a very different character from the one in America, to redeem the name of Cox from the infamy that must necessarily settle down upon the head of that Cox, who, with wiles and subtlety, led the Evangelical Alliance astray upon this question. [Cheers.] I am glad—I am delighted—I am grateful— profoundly grateful, in review of all the facts, that my friend—the slave’s friend—Dr. Cox of Hackney, has been pleased to give us his presence to-night. [Renewed cheers.] But now, really if the slaveholder is watching for an opportunity to get rid of his slaves, what has he to do? Why, just nothing at all—he has only to cease to do. He has to undo what he has already done; nothing more. He has only to tell the slave, “I have no longer any claim upon you as a slave.” That is all that is necessary; and then the work is done. The Negro, simple in his understanding as he was represented this evening—somewhat unjustly, by the by [referring to some remarks made in a former part of the evening by the vocalist, Mr. Henry Russell]—would take care of the rest of the matter. He would have no difficulty in finding some way to gain his freedom, if his master only gave him permission so to do. The truth is, that the whole of America is cursed with slavery. There is upon our Northern and Western borders a land uncursed by slavery—a territory ruled over by the British power. There—

The lion at a virgin’s feet

Crouches, and lays his mighty paw

Upon her lap—an emblem meet

Of England’s queen and England’s law. [Cheers.]

From the slave plantations of America the slave could run, under the guidance of the North-star, to that same land, and in the mane of the British lion he might find himself secure from the talons and beak of the American eagle. The American slave-holder has only to say to his slave, “To-morrow, I shall no longer hold you in bondage,” and the slave forthwith goes, and is permitted—not merely “permitted”—oh! no, he is welcomed and received with open arms, by the British authorities; he is welcomed, not as a slave, but as a man; not as a bondman, but as a freeman; not as a captive, but as a brother. [Cheers.] He is received with kindness, and regarded and treated with respect as a man. The Americans have only to say to their slaves, “Go and be free;” and they go and are free. No power within the states, or out of the states, attempts to disturb the master in the exercise of his right of transferring his Negro from one country to the other. “Oh! but then,” Dr. Cox would say, “brethren, although all this which Douglass states may be very true, yet you must know that there are some very poor masters, who are so situated in regard to pecuniary matters”—for the doctor is a very indirect speaker—”so situated, in regard to pecuniary concerns, that they would not be able to remove their slaves. I know a brother in the South—a dear brother” (Mr. Douglass here imitated the tone and style of Dr. Cox, in a manner which caused great laughter) “to whom I spoke on this subject; and I told him what a great sin I thought it was for him to hold slaves; but he said to me, ‘Brother, I feel it as much as you do, [loud laughter], but what can I do? Here are my slaves; take them; you may have them; you may take them out of the state if your please.’ Said he, “I could not; and I left them. [Renewed laughter.] Now what would you do?” said the doctor to the brethren at Manchester and Liverpool—”what would you do, if placed in such difficult circumstances?” The fact is, there is no truth in the existence of these difficulties at all. Sir, let me tell you what has stood as a standing article in our anti-slavery journals for the last ten years. When this plea was first put forth in America, and those intrepid champions of the slave, Gerrit Smith, Arthur Tappan, and other noble-minded abolitionists heard of it, what did they do? They inserted their cards in all the most respectable papers in America, and stated that there were 10,000 dollars ready at the service of any poor slaveholders who might not have the means of removing the Negroes they were desirous of emancipating. [Cheers.] Now, sir, the slaveholders must have seen this advertisement, for whatever difficulties they have to encounter, they find none in seeing money. [Hear, and laughter.] But, sir, was there ever a demand for a single red copper of the whole of those 10,000 dollars? Never; never. Now what does this fact prove? Why that there were no slaveholders who stood in need of such assistance; not one who wanted it for the purpose for which it might have been easily obtained, to meet the “difficult circumstances” stated by Dr. Cox. How Dr. Cox could, knowing that fact, as he must have done—for he is not so blind that he cannot see a dollar—I say how he could set up this false and contemptible plea before the world, and attempt to mislead the public mind of England upon the subject—I will not use a harsh expression, but I will say—that I cannot see how he could reconcile its concealment with honesty at any rate. That is the strongest word I will use in regard to this portion of his conduct. [Hear, hear.] He certainly knew better; at least, I think he must have known better; he ought to have done so; for it is astonishing how quickly he sees things generally. Another brother, the Reverend Doctor Marsh, also went into this subject, and told the brethren of the difficult circumstances in which the slaveholders were placed, especially the “Christian slaveholders;” for, mark this, they never apologise for infidel slaveholders! [Hear.] You never heard one of the whole deputation apologise for that brutal man—the uneducated slavedriver. No; it is the refined, polite, highly civilised, genteel, Christian part of the slaveholders, for whom they stand up and plead. Yes; they apologise for what they call “Christian slaveholders”—white blackbirds! [Loud cheers and laughter.]

Dr. Marsh stated, that if any persons in the United States were to emancipate their slaves, they would instantly be put into the penitentiary. [Laughter, and cries of “Oh, oh.”] I have sometimes been astonished at the credulity of their English auditory; but I do not wonder at it, for John Bull is pretty honest himself, and he thinks other people are so also. But, yet, I must say that I am surprised when I find sagacious, intelligent men really carried away by such assertions as these. Why, sir, if this statement were true, another tinge, deeper and darker than any previously exhibited, would have appeared in the character of the American people. What! men are not only permitted to enslave, not only allowed by the government to rob and plunder, but actually compelled by the first government upon earth to live by plunder! Why, these men, by such statements, stamp their country with an infamy deeper than I can cast upon it by anything I could say; that is, admitting their statements were true. But, sir, America, deeply fallen and lost as she is to moral principle, has not embodied in the form of law any such compulsion of slavery as that which these reverend gentlemen attempt to make out. No, sir; the slaveholder can free his slaves. Why, he has the same right to emancipate as he has to whip his Negro. He whips him; he has a right to do what he pleases with his own; he may give his slave away. I was given away [hear]; I was given away by my father, or the man who was called my father, to his own brother. My master was a methodist class-leader. [Hear.] When he found that I had made my escape, and was a good distance out of his reach, he felt a little spark of benevolence kindled up in his heart; and he cast his eyes upon a poor brother of his—a poor, wretched, out-at-elbows, hat-crown-knocked-in brother [laughter]—a reckless brother, who had not been so fortunate as to possess such a number of slaves as he had done. Well, looking over the pages of some British newspaper, he saw his son Frederick a fugitive slave in a foreign country, in a state of exile; and he determined now, for once in his life, that he would be a little generous to this brother out at the elbows, and he therefore said to him, “Brother, I have got a Negro; that is, I have not got him, but the English have [cheers]. When a slave, his name was Frederick—Fred. Bailey. We called him Fred” (for the Negroes never have but one name); “but he fancied that he was something better than a slave, and so he gave himself two names. Well, that same Fred. is now actually changed into Frederick Douglass, and is going through the length and breadth of Great Britain, telling the wrongs of the slaves. Now, as you are very poor, and certainly will not be made poorer by the gift I am about to bestow upon you, I transfer to you all legal right to property in the body and soul of the said Frederick Douglass.” [Laughter.] Thus was I transferred by my father to my uncle. Well, really, after all, I feel a little sympathy for my uncle, Hugh Auld. I did not wish to be altogether a losing game for Hugh, although, certainly, I had no desire myself to pay him any money; but if any one else felt disposed to pay him money, of course they might do so. But at any rate I confess I had less reluctance at seeing £150 paid to poor Hugh Auld than I should have had to see the same amount of money paid to his brother, Thomas Auld, for I really think poor Hugh needed it, while Thomas did not. Hugh is a poor scamp. I hope he may read or hear of what I am now saying. I have no doubt he will, for I intend to send him a paper containing a report of this meeting.

By-the-by, though, I want to tell the audience one thing which I forgot, and that is, that I have as much right to sell Hugh Auld as Hugh Auld had to sell me. If any of you are disposed to make a purchase of him, just say the word. [Laughter.] However, whatever Hugh and Thomas Auld may have done, I will not traffic in human flesh at all; so let Hugh Auld pass, for I will not sell him. [Cheers.] As to the kind friends who have made the purchase of my freedom, I am deeply grateful to them. I would never have solicited them to have done so, or have asked them for money for such a purpose. I never could have suggested to them the propriety of such an act. It was done from the prompting or suggestion of their own hearts, entirely independent of myself. While I entertain the deepest gratitude to them for what they have done, I do not feel like shouldering the responsibility of the act. I do, however, believe that there has been no right or noble principle sacrificed in the transaction. Had I thought otherwise, I would have been willingly “a stranger and a foreigner, as all my fathers were,” through my life, in a strange land, supported by those dear friends whom I love in this country. I would have contented myself to have lived here rather than have had my freedom purchased at the violation or expense of principle. But, as I said before, I do not believe that any good principle has been violated. If there is anything to which exception may be taken, it is in the expediency, and not the principle, involved in the transaction. I wish to say one word more respecting another body who have been alluded to this evening. You see that I keep harping on the church and its ministers, and I do so for the best of all reasons, that however low the ministry in a country may be (they may take this admission and make what they can of it: I know they will interpret it in their own favour, as it may be so interpreted)—that however corrupt the stream of politics and religion, nevertheless the fountain of the purity, as well as of the corruption, of the community may be found in the pulpit. (Hear.) It is in the pulpit and the press—in the publications especially of the religious press—that we are to look for our right moral sentiment. [Hear, hear.] I assert this as my deliberate opinion, I know, against the views of many of those with whom I co-operate. I do believe, however dark and corrupt they may be in any country, the ministers of religion are always higher—of necessity higher—than the community about them. I mean, of course, as a whole. There are exceptions. They cannot be enunciating those great abstract principles of right without their exerting, to some extent, a healthy influence upon their own conduct, although their own conduct is often in violation of those great principles. I go, therefore, to the churches, and I ask the churches of England for their sympathy and support in this contest. Sir, the growing contact and communication between this country and the United States, renders it a matter of the utmost importance that the subject of slavery in America should be kept before the British public. [Hear.] The reciprocity of religious deputations— the interchange of national addresses—the friendly addresses on peace and upon the subject of temperance—the ecclesiastical connections of the two countries— their vastly increasing commercial intercourse resulting from the recent relaxation of the restrictive laws upon the commerce of this country—the influx of British literature into the United States as well as of American literature into this country—the constant tourists—the frequent visits to America by literary and philanthropic men—the improvement in the facility for the transportation of letters through the post-office, in steam navigation, as well as other means of locomotion—the extraordinary power and rapidity with which intelligence is transmitted from one country to another—all conspire to make it a matter of the utmost importance that Great Britain should maintain a healthy moral sentiment on the subject of slavery. Why, sir, does slavery exist in the United States? Because it is reputable: that is the reason. Why is it thus reputable in America? Because it is not so disreputable out of America as it ought to be. Why, then, is it not so disreputable out of the United States as it should be? Because its real character has not been so fully known as it ought to have been. Hence, sir, the necessity of an Anti-slavery League [Hear, hear, and cheers]—of men leaguing themselves together for the purpose of enlightening, raising, and fixing the public attention upon this foulest of all blots upon our common humanity. Let us, then, agitate this question. [Hear.] But, sir, I am met by the objection, that to do so in this country, is to excite, irritate, and disturb the slaveholder. Sir, this is just what I want. I wish the slaveholder to be irritated. I want him jealous: I desire to see him alarmed and disturbed. Sir, by thus alarming him, you have the means of blistering his conscience, and it can have no life in it unless it is blistered. Sir, I want every Englishman to point to the star-spangled banner and say—

United States! Your banner wears

Two emblems, one of fame:

Alas! the other that it bears

Reminds us of your shame,

The white man’s liberty in types

Stands blazoned on your stars;

But what’s the meaning of your stripes?

They mean your Negroes’ scars.

“Oh!” it is said, “but by so doing you would stir up war between the two countries.” Said a learned gentleman to me, “You will only excite angry feelings, and bring on war, which is a far greater evil than slavery.” Sir, you need not be afraid of war with America while they have slavery in the United States. We have 3,000,000 of peace-makers there. Yes, 3,000,000, sir—3,000,000 who have never signed the pledge of the noble Burrit, but who are, nevertheless, as strong and as invincible peace-men as even our friend Elihu Burrit himself. Sir, the American slaveholders can appreciate these peace-makers: 3,000,000 of them stand there on the shores of America, and when our statesmen get warm, why these 3,000,000 keep cool. [Laughter]. When our legislators’ tempers are excited, these peace-makers say, “Keep your tempers down, brethren!” The Congress talks about going to war, but these peace-makers suggest, “But what will you do at home?” When these slaveholders declaim about shouldering their muskets, buckling on their knapsacks, girding on their swords, and going to beat back and scourge the foreign invaders, they are told by these friendly monitors, “Remember, your wives and children are at home! Reflect that we are at home! We are on the plantations. You had better stay at home and look after us. True, we eat the bread of freemen; we take up the room of freemen; we consume the same commodities as freemen: but still we have no interest in the state, no attachment for the country: we are slaves! You cannot fight a battle in your own land, but, at the first tap of a foreign drum—the very moment the British standard shall be erected upon your soil, at the first trumpet-call to freedom—millions of slaves are ready to rise and to strike for their own liberty.” [Loud cheers.] The slaveholders know this; they understand it well enough. No, no; you need not fear about war between Great Britain and America. When Mr. Polk tells you that he will have the whole of Oregon, he only means to brag a little. When this boasting president tells you that he will have all that territory or go to war, he intends to retract his words the first favourable opportunity. When Mr. Webster says, fiercely, If you do not give back Madison Washington—the noble Madison Washington, who broke his fetters on the deck of the Creole, achieved liberty for himself and one hundred and thirty-five others, and took refuge within your dominions—when this proud statesman tells you, that if you do not send this noble Negro back to chains and slavery, he will go to war with you, do not be alarmed; he does not mean any such thing. Leave him alone; he will find some way—some diplomatic stratagem almost inscrutable to the eyes of common men—by which to take back every syllable he has said. [Hear, hear.] You need not fear that you will have any war with America while slavery lasts, and while you as a people maintain your opposition to the accursed system. When you cease to feel any hostility to slavery, the slave-holders will then have no fear that the slaves will desert them for you, or will hate and fight against them in favour of you. So that, if only as a means of preserving peace, it were wise policy to advocate in England the cause of the emancipation of the American slaves. But, sir, England not only has power to do great good in this matter, but it is her duty to do so to the utmost of her ability. But I fear I am speaking too long. [Loud cheers, and cries of “No, no”; “Go on, go on.”] Oh, my friends, you are very kind, but you are not very wise in saying so, allow me to tell you, with all due deference.

I must conclude, and that right early; for I have to speak again to-morrow night almost 200 miles from this place; and it becomes necessary, therefore, that I should bring my address to a close, if only from motives of self-preservation, which the Americans say is the first law of slavery. But before I sit down, let me say a few words at parting to my London friends, as well as those from the country, for I have reason to believe that there are friends present from all parts of the United Kingdom. I look around this audience, and I see those who greeted me when I first landed on your soil. I look before me here, and I see representatives from Scotland, where I have been warmly received and kindly treated. Manchester is represented on this occasion, as well as a number of other towns. Let me say one word to all these dear friends at parting; for this is probably the last time I shall ever have an opportunity of speaking to a British audience, at all events in London. I have now been in this country nineteen months, and I have travelled through the length and breadth of it. I came here a slave. I landed upon your shores a degraded being, lying under the load of odium heaped upon my race by the American press, pulpit, and people. I have gone through the wide extent of this country, and have steadily increased—you will pardon me for saying so, for I am loath to speak of myself—steadily increased the attention of the British public to this question. Wherever I have gone, I have been treated with the utmost kindness, with the greatest deference, the most assiduous attention; and I have every reason to love England. Sir, liberty in England is better than slavery in America. Liberty under a monarchy is better than despotism under a democracy. [Cheers.] Freedom under a monarchical government is better than slavery in support of the American capitol. Sir, I have known what it was for the first time in my life to enjoy freedom in this country. I say that I have here, within the last nineteen months, for the first time in my life, known what it was to enjoy liberty. I remember, just before leaving Boston for this country, that I was even refused permission to ride in an omnibus. Yes, on account of the colour of my skin, I was kicked from a public conveyance just a few days before I left that “cradle of liberty.” Only three months before leaving that “home of freedom,” I was driven from the lower floor of a church, because I tried to enter as other men, forgetting my complexion, remembering only that I was a man, thinking, moreover, that I had an interest in the gospel there proclaimed; for these reasons I went into the church, but was driven out on account of my colour. Not long before I left the shores of America I went on board several steamboats, but in every instance I was driven out of the cabin, and all the respectable parts of the ship, onto the forward deck, among horses and cattle, not being allowed to take my place with human beings as a man and a brother. Sir, I was not permitted even to go into a menagerie or to a theatre, if I wished to have gone there. The doors of every museum, lyceum and athenaeum were closed against me if I wanted to go into them. There was the gallery, if I desired to go. I was not granted any of these common and ordinary privileges of free men. All were shut against me. I was mobbed in Boston, driven forth like a malefactor, dragged about, insulted, and outraged in all directions. Every white man—no matter how black his heart—could insult me with impunity. I came to this land—how greatly changed! Sir, the moment I stepped on the soil of England—the instant I landed on the quay at Liverpool—I beheld people as white as any I ever saw in the United States; as noble in their exterior, and surrounded by as much to commend them to admiration, as any to be found in the wide extent of America. But, instead of meeting the curled lip of scorn, and seeing the fire of hatred kindled in the eyes of Englishmen, all was blandness and kindness. I looked around in vain for expressions of insult. Yes, I looked around with wonder! for I hardly believed my own eyes. I searched scrutinizingly to find if I could perceive in the countenance of an Englishman any disapprobation of me on account of my complexion. No; there was not one look of scorn or enmity. [Loud cheers.] I have travelled in all parts of the country: in England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. I have journeyed upon highways, byways, railways, and steamboats. I have myself gone, I might say, with almost electric speed; but at all events my trunk has been overtaken by electric speed. In none of these various conveyances, or in any class of society, have I found any curled lip of scorn, or an expression that I could torture into a word of disrespect of me on account of my complexion; not one. Sir, I came to this city accustomed to be excluded from athenaeums, literary institutions, scientific institutions, popular meetings, from the colosseum—if there were any such in the United States—and every place of public amusement or instruction. Being in London, I of course felt desirous of seizing upon every opportunity of testing the custom at all such places here, by going and presenting myself for admission as a man. From none of them was I ever ejected. I passed through them all; your colosseums, museums, galleries of painting, even into your House of Commons; and, still more, a nobleman—I do not know what to call his office, for I am not acquainted with anything of the kind in America, but I believe his name was the Marquis of Lansdowne—permitted me to go into the House of Lords, and hear what I never heard before, but what I had long wished to hear, but which I could never have heard anywhere else, the eloquence of Lord Brougham. In none of these places did I receive one word of opposition against my entrance. Sir, as my friend Buffum, who used to travel with me, would say, “I mean to tell these facts, when I go back to America.” [Cheers.] I will even let them know, that wherever else I may be a stranger, that in England I am at home. [Renewed cheering.] That whatever estimate they may form of my character as a human being, England has no doubt with reference to my humanity and equality. That, however much the Americans despise and affect to scorn the Negroes, that Englishmen—the most intelligent, the noblest and best of Englishmen—do not hesitate to give the right hand of fellowship, of manly fellowship, to a Negro such as I am. I will tell them this, and endeavour to impress upon their minds these facts, and shame them into a sense of decency on this subject. Why, sir, the Americans do not know that I am a man. They talk of me as a box of goods; they speak of me in connexion with sheep, horses, and cattle. But here, how different! Why, sir, the very dogs of old England know that I am a man! [Cheers.] I was in Beckenham for a few days, and while at a meeting there, a dog actually came up to the platform, put his paws on the front of it, and gave me a smile of recognition as a man. [Laughter.] The Americans would do well to learn wisdom upon this subject from the very dogs of Old England; for these animals, by instinct, know that I am a man; but the Americans somehow or other do not seem to have attained to the same degree of knowledge. But I go back to the United States not as I landed here—I came a slave; I go back a free man. I came here a thing—I go back a human being. I came here despised and maligned—I go back with reputation and celebrity; for I am sure that if the Americans were to believe one tithe of all that has been said in this country respecting me, they would certainly admit me to be a little better than they had hitherto supposed I was. I return, but as a human being in better circumstances than when I came. Still I go back to toil. I do not go to America to sit still, remain quiet, and enjoy ease and comfort. Since I have been in this land I have had every inducement to stop here. The kindness of my friends in the north has been unbounded. They have offered me house, land, and every inducement to bring my family over to this country. They have even gone so far as to pay money, and give freely and liberally, that my wife and children might be brought to this land. I should have settled down here in a different position to what I should have been placed in the United States. But, sir, I prefer living a life of activity in the service of my brethren. I choose rather to go home; to return to America. I glory in the conflict, that I may hereafter exult in the victory. I know that victory is certain. [Cheers.] I go, turning my back upon the ease, comfort, and respectability which I might maintain even here, ignorant as I am. Still, I will go back, for the sake of my brethren. I go to suffer with them; to toil with them; to endure insult with them; to undergo outrage with them; to lift up my voice in their behalf; to speak and write in their vindication; and struggle in their ranks for that emancipation which shall yet be achieved by the power of truth and of principle for that oppressed people. [Cheers.] But, though I go back thus to encounter scorn and contumely, I return gladly. I go joyfully and speedily. I leave this country for the United States on the 4th of April, which is near at hand. I feel not only satisfied, but highly gratified, with my visit to this country. I will tell my colored brethren how Englishmen feel for their miseries. It will be grateful to their hearts to know that while they are toiling on in chains and degradation, there are in England hearts leaping with indignation at the wrongs inflicted upon them. I will endeavour to have daguerreotyped on my heart this sea of upturned faces, and portray the scene to my brethren when I reach America; I will describe to them the kind looks, the sympathetic desires, the determined hostility to everything like slavery sitting heavily or beautifully on the brow of every auditory I have addressed since I came to England. Yes, I will tell these facts to the Negroes, to encourage their hearts and strengthen them in their sufferings and toils; and I am sure that in this I shall have your sympathy as well as their blessing. Pardon me, my friends, for the disconnected manner in which I have addressed you; but I have spoken out of the fulness of my heart; the words that came up went out, and though not uttered altogether so delicately, refinedly, and systematically as they might have been, still, take them as they are—the free upgushings of a heart overborne with grateful emotions at the remembrance of the kindness I have received in this country from the day I landed until the present moment. With these remarks I beg to bid all my dear friends, present and at a distance—those who are here and those who have departed—farewell!

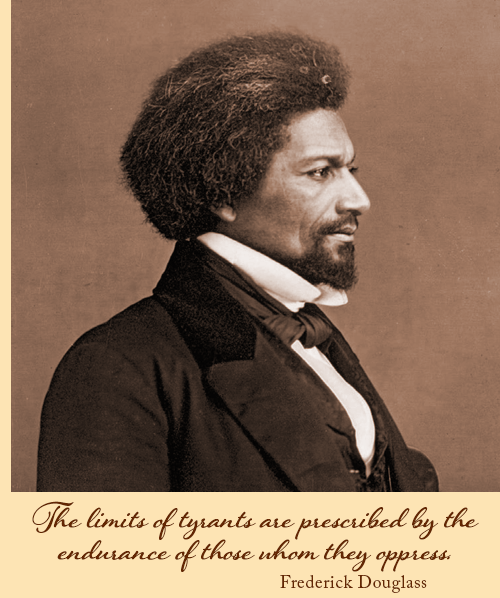

Frederick Douglass was one of the most prolific writers os the 19th century. He wrote three autobiographies, each one expanding on the details of his life. The first was Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written By Himself (1845); the second was My Bondage and My Freedom (1855); and the third was Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881). They are now foremost examples of the American slave narrative. After escaping from slavery, Douglass began giving speeches about his life and experiences. His first autobiography brought him fame throughout the United States and the United Kingdom. Douglass founded his first paper, the North Star. He served as its chief editor and authored a considerable body of letters, editorials, and speeches from then on.

We present a number of his writings here and will add more over time. His writings have been collected in many volumes and many are also available on the Library of Congress website.

The Church and Prejudice

- November 4, 1841

Farewell Speech to the British People - March 30, 1847

What to the Slave is the Fourth of July? - July 5, 1852

A Call To Work - November 19, 1852